Shark Med is a not-for-profit association established in 2017 and dedicated to the study and conservation of sharks in the western Mediterranean, particularly in the Balearics. Here we talk to its president, Agustí Torres.

Tell us about your professional career?

I’ve been a professional photographer and documentary-maker since 1983. I studied photography as part of a fine arts course and I have exhibited in New York, Paris, Madrid and Rome. These artworks, that I’ve always combined with my professional life, have always been directly or indirectly related to a critical analysis of our relationship with the environment. The graduate thesis I did at the University of Derby in England analysed the way nature is currently portrayed in the media. My conclusions weren’t very optimistic. Often the images taken by nature photographers have the opposite effect to what was intended. Later, in the United States, my post-graduate thesis was a critical analysis of the globalisation of consumer society and its devastating impact on the environment. That’s why my artistic photographic exhibitions have always had more to do with conceptual and critical aspects than with landscape or marine life. My view is that, while there are many people with a high level of technique and aesthetics who want to reveal the beauty, richness and spectacle of nature, there aren’t many willing or able to carry out an exercise in self-criticism of audio-visual language which is also necessary in a society where this language has increasing influence and consequences.

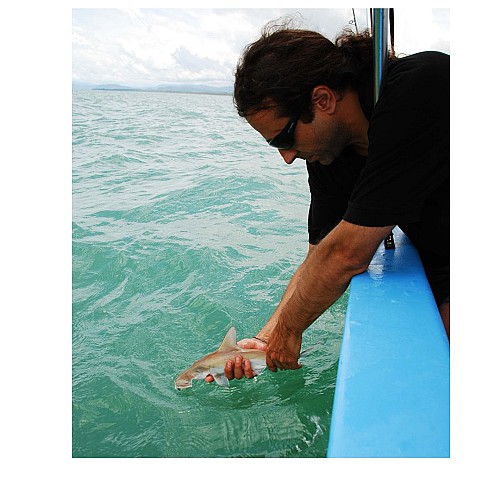

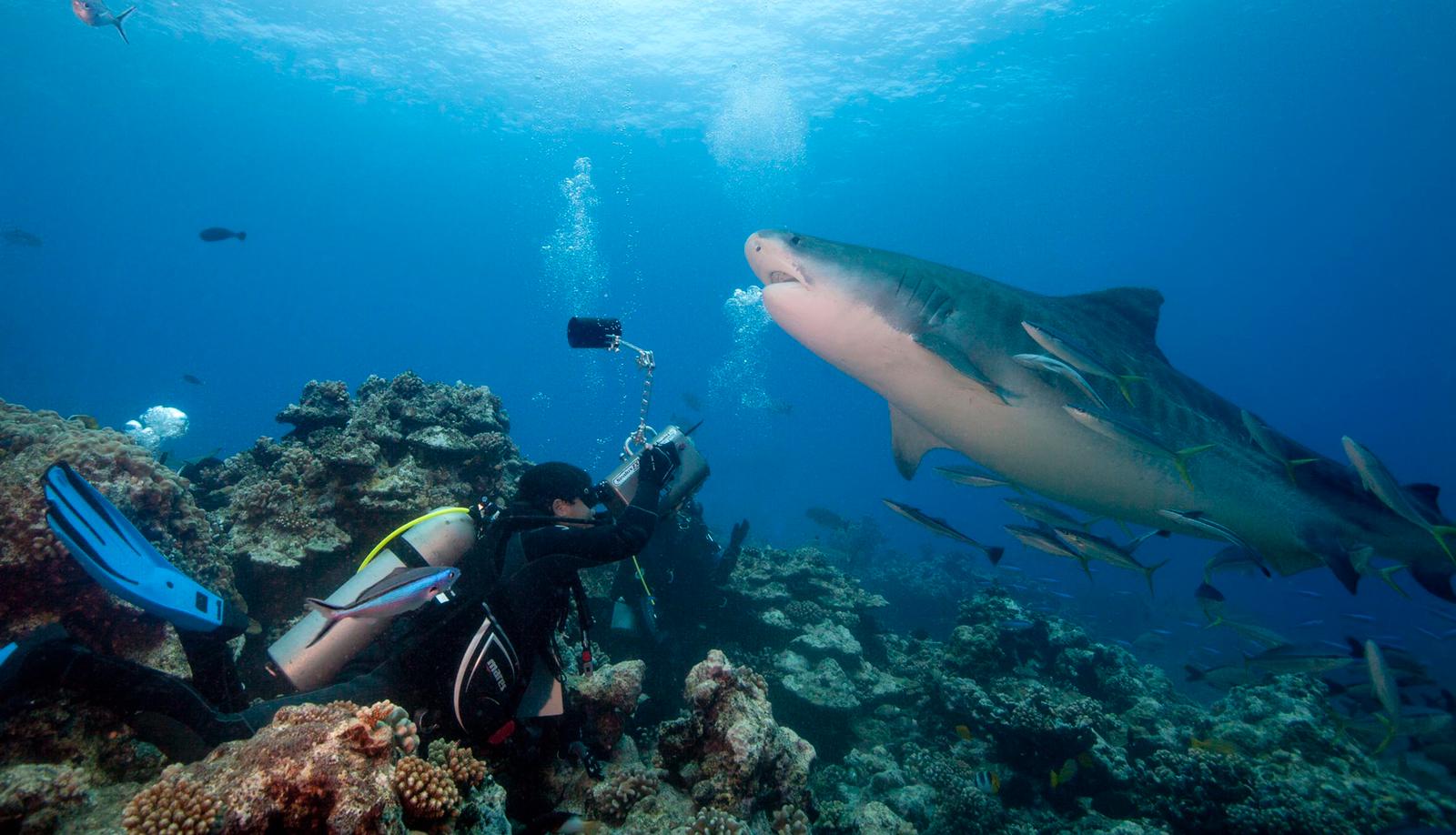

In my case, underwater photography has always been a passion rather than a professional speciality, together with a love of the sea and my interest in audio-visual expression. That said, thanks to my technical professional knowledge, I’ve been involved in filming various scientific documentaries in many parts of the Pacific, alongside my friend Professor Eric Clua.

Agustí Torres with a female tiger shark in Tahiti, French Polynesia.

How did the Shark Med project come about?

As soon as the Covid-19 restrictions end we’re going to launch an ambitious research project in all the Balearic Isles that will combine the financial backing of the Marilles Foundation and the collaboration of Shark Med with the following organisations and scientists: Biel Morey and Save the Med in Mallorca; Manu San Félix and the Asociación Vellmarí in Ibiza and Formentera; our very own Sergi Escandell with the producer Paleártica Films in Menorca..

I worked on various projects in the Pacific Ocean with Eric Clua, one of the world’s leading shark experts. We’ve been close friends since childhood and have a shared passion for the sea and Mallorca. At some point it occurred to us that, since we work with these animals there, why not here, where the situation is much more serious and where there’s a large gap in empirically-based scientific knowledge. We suggested the idea to Dr Ana María Abril at the Universitat de les Illes Balears and Shark Med was born as the basis for collaboration between that university and the Université de Perpignan where Clua works.

The biggest challenge was finding out if direct observation was even possible given that, in waters with such a low density of shark populations, it would be like looking for a needle in a haystack. As a result, we spent the first few years developing methods of attracting, filming and even interacting with them. The pilot phase produced very good results and led to the methodology being published in the Journal of Marine Science and Engineering,a Swiss scientific journal.

Our team also includes Sergi Escandell, a well-known underwater film-maker, and the veterinarian Maria Magdalena Adrover.

The idea is to begin a period of intensive research into scientific data and images that will help us assess the sharks current state and to push for the introduction of mechanisms to boost the recovery and sustainability of the species. At the moment it’s vital to work in the scientific field while using audio-visual media to raise awareness and gain support.

Why sharks and not other species? What made you decide to get involved in a project about sharks?

When I realised how little the problem was understood, I decided to do something to try to improve the situation. We feel closer to marine mammals and there have been organisations dedicated to protecting them for a long time, but there are very few that focus on sharks. My colleagues and I are aware that there’s a lot of work to be done, in both research and education..

Over-fishing of sharksis endangering other species around the world and in the Mediterranean the situation is especially alarming. The Ferreti scientific study carried out in 2008 warned that between 96% and 99,99% of the 47 Mediterranean species had disappeared. Twelve years later there is no reason to think things have got better, on the contrary. We are at a critical point and if we don’t act soon the situation may be irreversible.

We were talking about the negative impact that images can have and the fact is this over-fishing has partly been justified by the shark’s undeserved reputation as a dangerous animal thanks to films like Jaws and other myths. Up until now people have viewed the big predators on land and sea as a threat and a competitor in the hunt for food. This has led to the disappearance of wolves, bears and our monk seal. Now we know scientifically that this has been a serious mistake. We know that predators play a very important and beneficial role in the health of all ecosystems. When a part of the food chain disappears or is debilitated it produces an imbalance that can jeopardise the existence of the entire system. It’s a domino effect so that species lower down the chain proliferate and prey massively on others and this often leads to an over-exploitation of resources and the desertification of the habitat. We also know that sharks don’t see humans as food and that the number of fatal accidents produced by sharks is merely anecdotal compared to many others in everyday life. Every day thousands of people dive among sharks around the world’s coasts in complete safety.

Where does your relationship with and appreciation of the sea stem from? When did you begin filming in the sea?

I discovered the sea world when I was very young, with my father and my friends. As we grow up and become physically more adept it gives us the chance to discover a world that is endlessly surprising. It was like constantly discovering a new and exotic land. The fascinating beauty of nature, and the sea especially, is what makes everything make sense to me. Like many biologists and marine photographers, I started out with underwater fishing, but I grew up during the tourist boom and when I saw how it was destroying what I love I gave up fishing and started to work towards protecting marine life through, among other things, the artworks that I mentioned earlier.

How do you think we can improve marine conservation in the Balearics?

In the Balearics we live in a marvellous environment, both on land and in the sea, but we’re constantly in danger of being victims of our own success. The challenge is to understand how far we’re degrading our environment if we continue with this greedy and destructive system. Our waters and the creatures that live in them are affected not just by over-fishing but also by pollution caused by a lack of infrastructure and through failing to take necessary measures. It’s vital that everyone understands that the road we’ve followed so far will only deliver food today and hunger tomorrow. If the environment collapses, we will collapse with it. There are difficult times ahead. Covid 19 is going to lead to a major economic crisis and in the past, when we’ve gone through economic hardship, environmental issues have tended to be sidelined. We’ve seen how easily people like Trump and Bolsonaro emerge, bent on creating wealth and jobs at any price. We can’t let this happen. The current crisis should serve to redirect our economy and rethink industries in order to make them more sustainable. It’s a warning but also an opportunity.

The marine reserves are an encouraging sign but we have much less protection than scientific studies recommend. That’s why it’s important to create more. In the end, the fishermen are the ones who will benefit most. One of the first things Shark Med revealed is the high incidence of bycatch in shark populations. This shows that it’s not enough to have laws that protect specific species. If the laws aren’t associated with technical control measures to avoid the situation where the fishing of one species has a negative effect on others, protection is worthless. The hooks found in blue sharks are mostly hooks used to fish for swordfish. When a fisherman catches a blue shark he cuts the line and leaves it wounded, seriously affecting its chances of survival despite being set free. And we’re always finding dead bluntnose sharks on the coast that have been caught up in trawler nets. That’s why it’s so important to encourage good practice in fishing to avoid this sort of collateral damage. We have to extend protection to more species and find safer ways of throwing accidental catch back into the sea. For example, some countries have banned stainless steel hooks because they’ve found that non-stainless ones decay and fall out in a relatively short period of time whereas stainless hooks remain stuck in the animal for years.

Many of those with vested interests like to compare ecologists with apocalyptic religious fanatics, but the difference is that our views have a scientific basis. Recovering marine reserves is like a mirage in the middle of an enormous desert of negative statistics. We live in a society with some unfortunate paradoxes, such as that tourism appears to be the only alternative to destruction. Even we conservationist groups argue that tourism helps to generate nature reserves as a means of persuading politicians and business. However, tourism is also one of the industries that contributes most to the greenhouse effect and the destruction of cultures and habitats. As I said, we have our work cut out trying to resolve these types of contradictions.

What’s the lockdown been like for you?

I like to go walking in the mountains but I also love having time at home to do things I don’t normally get around to, such as reading and cooking. I’ve taken the opportunity to do an online course in Arduino, a micro-controller that will help us to improve our BRUVS’ measurement and automation systems. I’ve been listening to a lot of French radio to improve my level. And I’ve been able to follow and take part in webinars from Save the Med and other conservation groups.

I’ve also been fortunate that I was allowed out for work at IB3 and TVE television. It’s been possible to see and document what all the empty villages, roads and beaches look like now that time has stood still, and that’s been a real privilege. I would have liked to have seen what was going on underwater but it hasn’t been possible.

Quick test for sea lovers

A book: Collapse, by Jared Diamond.

An image you associate with the Balearics: When I was a kid my father used to take me hunting in what is now the Parque Natural de Llevant. Whenever we climbed the last hill and had a view of that virgin coast, I always thought I was looking at paradise. It’s an image that’s stayed with me all my life.

A marine species: The blue shark, Prionace glauca. Not being able to see one close up has made the lockdown seem very long.

An organization or person who is a role model: The GOB. An example of inter-generational struggle and perseverance.

A beach: It’s important to share but also to keep secrets and know how to discover things for ourselves. In other words, I’m not telling! (HaHa)

A phrase that defines you: I look for happiness in the little pleasures of everyday life, and put imagination and joy into all my projects. With this, everything else comes easily.Are you an optimist, realist or pessimist? I’m a pessimist who hopes he’s wrong and believes that with hard work we can change.